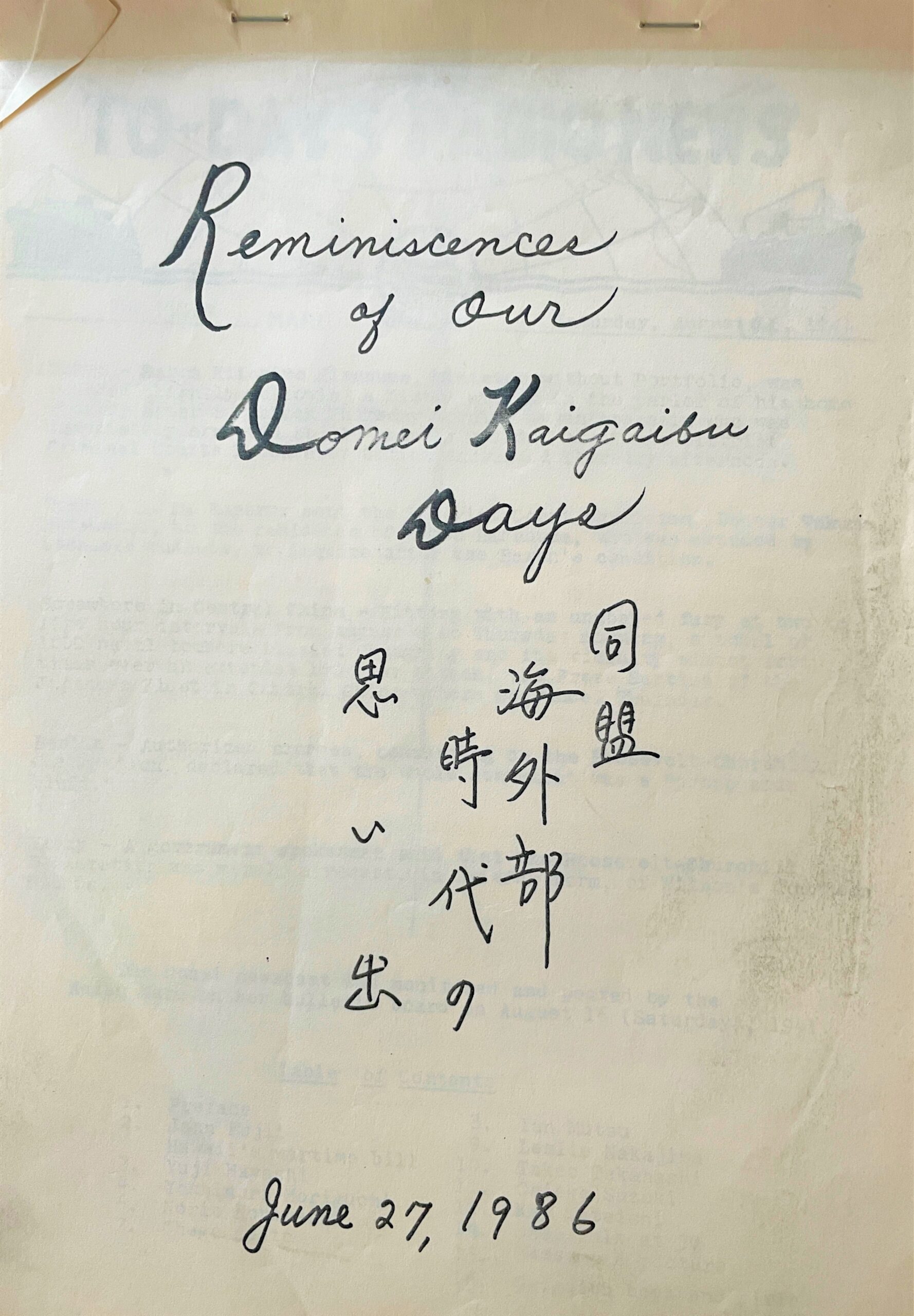

Reminiscences of the Domei News Agency Kaigaibu 1939-1945

“We Covered A Lost War”.

PREFACE 2022

By Olivier Fabre

I was rummaging through some of the few mementos I had of my Japanese grandparents when I came across a reunion newsletter written in 1987 by former journalists from the pre-war Japanese news agency Domei. My step-grandfather, Robert Yoshinori Horiguchi (堀口瑞典), was one such former journalist in the foreign news department of Domei (同盟) – the national news agency set up to rival AP or Reuters, the news agency I was to join in 1995. However, when I joined Reuters, Domei no longer existed in the form my grandparents knew back then. Soon after World War Two, General Douglas MacArthur deemed the news agency too powerful and split it into several media companies, with the news agency functions going to Jiji News Agency and Kyodo News Agency – both organizations still exist to this day.

Reading the testimonies from these journalists – many of whom were of mixed Japanese heritage or repatriates (as repatriated Nikkei (日系) or Nisei (二世) were called then) – many, like my step-grandfather, found themselves struggling to balance their identities and sometimes had to hide their true emotions amid the jingoistic juggernaut that was Imperial Japan during what they termed “an unfortunate and stupid four-year war.”

By 1986, my step-grandfather was already battling cancer that would take his life four years later. He never attended the reunion of his colleagues, and I wish I could have found them to ask the questions I never got to ask him before he passed away. Most of the names mentioned below would be nearing or surpassing 100 years of age today, so I have no illusion that I will actually meet any of them. However, please contact me if you or any of your relatives were colleagues of his or former members of the Domei News Agency Kaigaibu. (I have reproduced the newsletter as it was in the original printed version.)

PREFACE June 21, 1986

Four decades have slipped by from that momentous day Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945.

Scores of books and personal accounts on WWII by newsmen on the winning side have been published but hardly any on the losing side other than those written in Japanese by the Japanese.

Aside from these translations, stories of Japan and the war in Asia and the Pacific would be fascinating and thought-provoking, gloomy and exciting. They would undoubtedly reveal a lot and shed a different light on how it was working with the defeated.

Journalists like Johnny Fujii, Mas Ogawa, Les Nakajima, Bob Horiguchi, Day Inoshita, Ian Mutsu, the late Roy Otake, have often been quoted or interviewed by Americans, Europeans and others. However we feel the time has to tell the story as seen, experienced and written by those who shared the bleak, trying years, through agony and irony, working against tremendous odds. People capable of relating such narratives, we feel, are the OB members of Domei News Agency’s Kaigaibu (Overseas Bureau), who worked with the English language although they spoke and read Japanese.

Outsiders have often described Domei as a notorious government propaganda machine.

Undoubtedly it was. But to insiders Domei was referred to as Dame Tsushin-sha (Useless News Agency) which perhaps it was. The judgment however is yours to make.

Nevertheless, there are narratives that need to be told, that should be told, all important facets of wartime journalism. And unless they are written they may simply fade away with the passing years.

We hope the bits of reminiscences, anecdotes, happenings, related in this small reunion pamphlet will refresh memories and rekindle the desire to tell our side of an unfortunate and stupid four-year war.

We hope we are NOT being over-optimistic that a collection of personal stories on WWII in Asia and in Asia and the Pacific will appear soon.

Perhaps, titled “We Covered A Lost War”.

(KKT) June 21, 1986

John Fujii

From the No. 1 Shimbun, July 15, 1985

I was interrogated for two weeks and released after signing a statement. This was probably the first time that the Kempei-tai had a Japanese prisoner who could not write his statement in his mother tongue.

I had been raised in the States and never learned kanji.

During my questioning by the Kempei-tai, I was approached by a representative of Domei News Agency to join its staff in Singapore. I agreed since I had no other plans and the Domei people promised to keep me out of the hands of the Kempei-tai. I was probably the only Domei reporter who was recruited while a prisoner of the thought police.

John Fujii

http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2020/8/18/john-fujii-1/

Some of My Unpleasant Domei Days

By Yuji Hayashi

I returned to Japan from Hawaii in July, 1940. Fresh out of college, I aspired in my own way to change the world. Caught in the midst of the ugly geopolitical struggle between Japan and the United States, I was forced to make a great deal of accommodation with reality and to work within the existing order. Thick war clouds were then gathering fast over the Pacific. Three months later, I joined Domei and worked under Tasuku Sagara and Bob Horiguchi in the Gaiden-bu. A year later Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. My tendency toward amnesia about the war is strong and intentional. For that reason, it is not easy for me to recall my Domei days. The part of the war I am particularly reluctant to look back upon related, among others, the two occasions on each of which the wartime media manipulated my stories, blurring the essential distinction between covering news and creating news.

Early in 1942, when American prisoners of war arrived in Yokohama from Wake Island aboard a military transport, I was instructed to interview a number of officers and non-commissioned officers for the Japanese press and translate what they said. The coming of the prisoners was front paged in all major newspapers the following morning. I read what appeared in the papers and was appalled to find out that stories about them were sprinkled with statements and remarks not attributed to them.

In summer 1942, as a war correspondent, I was assigned to interview captured top Allied military commanders (among whom were the British Governor-generals of Malaya and Hongkong) near Karenko (Hualien), Taiwan. A couple of weeks later my stories made headlines in leading English-language papers published in the Japanese-occupied “Southern Region”, but to my regrets they were far from what I wrote. There was deep mourning inside me but I refrained from expressing how I felt.

At the time of surrender, I was with the Domei bureau in Bangkok. I worked for the British Information Service there as a civilian POW and returned home one year later.

—————————————

Reminiscences of Our Domei Days

I joined the Domei News Agency in November, 1939 to work in the English News Section (Eibun-bu). Next year, I was called up for military service as a medical private and sent to Peking.

Mr. Minoru Hattori, my senior in Eibun-bu, was serving at Domei’s Peking Office at that time. He recommended me to Lt. Col. Usaburo Nagai, deputy chief of the Information Division, the Japanese Expeditionary Force in North China, who was looking for a man capable of handling English news in his division. I was transferred to the information division. It brought me in uniform into close contacts daily with English news. This enabled me, when I was discharged from the military service two years later, to readapt myself without delay to the work at Domei’s English News Section.

In August, 1945, I was among English-proficient soldiers handpicked from all over the Kanto-Koshinetsu District for group training at the Main POW Camp at Omori, Tokyo. We trainees were destined, at the close of the training, to be attached to various divisions entrenched on the beaches of the Pacific Coast of Japan with a special mission to extort military secret information concerning the landing enemy forces from their high-ranking officers captured through interrogation in English. This tactics was devised by the desperate Imperial Headquarters faced with rapidly diminishing vital information sources abroad.

Norio Kobayashi

————————–

I joined Domei automatically as a result of the merger of the Rengo Tsushin-sha (Rengo) and the Nippon Dempo Tsushin-sha (Dentsu). I was then editor of the English service in the Shanghai bureau of Rengo, which I had joined in the fall of 1934 in Tokyo. I was first assigned to the gaishin-bu which at the time was headed by the late Seiji Hasegawa. My boss in Shanghai was Shigeharu Matsumoto and I had hired as rewrite man Mark Ginsburg, who after the war gained notoriety in Japan as the author of “Japan Diary” under the name of Mark Gayn.I was in Shanghai from the spring of 1935 to the summer of 1940, when I was reassigned to Tokyo where I worked in the gaiho-bu until the spring of 1941 when I was appointed correspondent to Madrid and Vichy. I was sent to Switzerland immediately after Pearl Harbor where I stayed until being repatriated in 1947.

Yoshinori Horiguchi

—————————-

A good reporter is always calm. Undisturbed by sudden disaster, he sets out efficiently to collect and report the facts. For him it is just another working day. Never emotional. Never editorial.

I must confess that I was nowhere near this category on that morning of Pearl Harbor when I showed up for work at Domei, in Nishi Ginza. It was war between the countries of my father and my mother. I had heard of such rumors but had dismissed them as impossible: Japan would never be so foolish as to invite, in the end, total defeat.

The atmosphere in the big newsroom was one of boisterous elation. Now Japan had drawn her sword. The West would be crushed and pax Japonica would prevail. I well remember the only dissenting voice, from a Nisei member of the Kaigaibu, Sam Hatai : “A big fireworks show before we crumble in defeat.” Dangerous words, even in a whisper, at the time.

For the first six months or so, up to about Guadalcanal, Domei’s outgoing news in English, as I remember, remained relatively factual. I watched in sadness as journalism, Domei English brand, deteriorated as a result of the fortunes of war turning against Japan.

On 19 November 1952 (typo in original, as Count Mutsu Hirokichi 陸奥 広吉 died November 19, 1942) my father died in Kamakura and it became my lot to inherit his title of count. Not too long after that I decided to quit Domei and spend the rest of the war years at our villa in Karuizawa. My neighbors there whom I occasionally met included some prominent people in Showa history : Prince Fumimaro Konoe, Shigenori Togo, Saburo Kurusu, Ichiro Hatoyama, etc, etc. All of them seemed to hope that the war would come to an end as soon as possible.

I listened to the Emperor’s surrender message with the radio in our garden along with other members of the household. In a few months I would be heading back to Tokyo to join the news staff of the United Press. Unexpectedly, I was given the status of “foreign correspondent” accredited to SCAP Headquarters General MacArthur’s and, in that role, resumed reporting Japan to the outside world.

I had joined Domei in May 1939 with the hope of helping to improve its overseas-bound news service. I resigned from Domei in May, 1943. I had been appointed head of the Kaigaibu on 8 August, 1941.

Ian Mutsu

Photo of Ian Mutsu in 1948 Asahi Graph

20 June 1986

——————————-

“Reminiscences of Our Domei Days” By Leslie Nakajima

I joined the Domei Kaigai-bu foreign desk, headed by Mr. Ian Mutsu, in February, 1942 which proved to be the salvation of my family during the war years.

Pearl Harbor on Dec. 8, 1941 threw me out of work as an American foreign correspondent for United Press (now United Press International). I had to find employment for the sustenance of my family, wife and two small daughters.

I first went to the Japan Times because I had come to Tokyo in May, 1934 to work on its copy desk through the goodwill of Managing Editor Yoshio Niitobe whom I had met in 1933 on my tour of Japan and Manchuria as a reporter of the Honolulu Star Bulletin. Mr. George Togasaki, then President of the Japan Times, tried to help me but could not get satisfactory clearance from the Police in hiring an enemy alien although of Japanese blood. I left Japan Times in May 1940 and became a U.P. foreign correspondent in Tokyo.

I learned that Mr. Mutsu was mustering the employment of English speaking people for Domei’s Kaigai-bu and went to him. He kindly suggested that I might get a job if I applied for Japanese nationality. I then consulted Robert Bellaire, U.P. Tokyo Bureau chief who had been rounded up by police with other American and British foreign correspondents on the morning of Pearl Harbor and taken for internment in Denenchofu. Six policemen from Harajuku Station searched my home the same morning but did not intern me. Bellaire said my first concern was my family and advised me not to hesitate applying for Japanese nationality under the circumstances.

I therefore made formal application for Japanese nationality in February, 1942 and Mr. Mutsu immediately hired me as a member of his staff where a number of American born Japanese people were working. When Mr. Togasaki learned that Domei had employed me; he very kindly said he could use me as a part time worker.

I made arrangements to work for Domei in the daytime and Japan Times at night. I continued on that basis until I resumed my job as U.P. foreign correspondent in August, 1945 when the war ended.

The people at both Domei and the Japan Times were very kind to me aware of my circumstances and I suffered no discrimination. I obtained my “koseki” (Japanese nationality) in June, 1942 and remember that my wife was relieved she was no longer “naisai” to the investigating police but “tsuma”.

It is such a long time ago my Domei days — that I cannot recall the names of the people I worked with. One afternoon, the Hibiya Public Hall ground floor where we worked shook badly as if struck by an earthquake. Many of us rushed out. A U.S. B-29 had dropped a bomb outside the building in the park. I saw a number of bodies of the dead being carried away by the police.

An Imperial Headquarters announcement, for the first time that I remember, admitted that the casualties were heavy from the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945 and that a “new weapon” (the atom bomb) had been used. The war ended on Aug. 15 with the Emperor’s surrender radio announcement.

A week or so later I obtained permission from Domei to go to Hiroshima to ascertain if my mother was still alive. Fortunately, she was. I had gone to Hiroshima on July 22 and evacuated my wife and two daughters to my wife’s friend’s evacuation quarters in Nagano prefecture.

I found Hiroshima had been razed to the ground by the atom bomb.

I had a story written of what I had seen in Hiroshima and gave it to a member of the U.P. war correspondents who swarmed into Tokyo after General MacArthur’s arrival. He took it back to a U.S. warship in Yokohama for transmission to New York. I was later told that it appeared in Time Magazine and newspapers as the first eye-witness account by a foreign correspondent of the Hiroshima atom bombing. A few days later, U.P. Vice President Frank Bartholomew, who also was a war correspondent, came to Domei and asked me to resume my job as U.P. foreign correspondent in Tokyo. With Domei’s permission, I immediately went to the reopened temporary U.P. Tokyo office in the old Mainichi Building near Yurakucho Station and worked for U.P. and later United Press International until my retirement at 73 in December, 1975.

———————————-

Dear Chugo

Thank you for arranging to get together. Will be there. I joined in 1939 (not sure, the year the Japan Advertiser folded). I was in Singapore in August 1945.

I remember my army conscription examination in Rangoon. Hasegawa, who was with Hikari Kiban had returned from the front with a hefty fever from malaria and we had to take him on a stretcher to the examination. John Fujii was there from the Navy. I was heishu gokahin? Army canceled my conscription examination on pressure from Domei and Mr Akuyama got me out of Burma in time. I heard that all the conscripts were forced into “Ran Butai” and died in Burma.

Takeo Takahashi

———————–

From Chieko Suzuki

同盟に入社したのは確か終戦の1年半前だと思います。はっきりした年月は覚えておりません。欧米部

終戦の8月は、戦争中とずっとおった。吉祥寺の現在地におりました。

空襲警報で市政会館の地下に避難した時小さな部屋にタイプを持ち込んで、空襲の情報を流しておりました。私の家から10分と離れてない、中島飛行機製作所に爆弾投下などと言うニュースを耳にした。毎日我が家はまだあるたろうかとビクビクしながら帰宅しました。

交通が途絶えて、あちこち歩いてい社に通ったお陰で足が (読めない)いなかった様です。

———————

For DOMEI Kaigaibu OB-kai from Kay K. Tateishi

One week before Pearl Harbor. I joined Domei on Dec. 1, together with George Kyotow (now residing in NY) and Biff Omori (died in the Philippines where he was buried by Mas Ogawa).

We were classmates at Heishikan (a small juku, financed by FO, Domei, KBS & two others) where we studied for two years on a scholarship. In Domei I worked in the English section of Kaigaibu (Overseas Bureau) under Ian Mutsu, whose staff already included Roy Otake, Ogawa, Chugo Koito, Inoshita, Hasegawa, Pete Takahashi, Nagahama, Mambo, Tak Ishii, Otsubo, Hatai. And already working overseas were Horiguchi and Ken Murayama.

I had to learn news service work from the ground up, deciphering and expanding cablese (which was Greek to me), translating and typing copy from romaji or Japanese from local papers garibanzuri. I struggled and got my tail chewed out for being slow.

The immediate reaction when war broke out in the Pacific was “Holy Christopher… we’re in it now… and there’s no chance of winning. Someone handed me a couple of foreign reports to work on. But I was in a daze, pecking at the typewriter. I felt as if I were in a make-believe world and war seemed like a fantasy and a page from science-fiction.

After six months of sweeping reports of victories, after the Battle of Midway they became inflated lies. The frantic ordeal to survive began. Koito and Otake were conscripted by the military forces. Ogawa was assigned to Manila Bureau of Domei. Inoshita to Shanghai. In early ‘42 the office moved from the Dentsu Bldg on the Ginza to Shisei-Kaikan in Hibiya Park. And the staff increased with recruits (they were refugees cut off from jobs with foreign firms or repats from abroad who had to eke out a living).

By the time air raids began, everyone had to wear gaiters with sufu national uniform, bulky pillow-like headgear with helmets (baggy mompei pantaloons for women).

Food was scarce so we drew lots for a late snack of zosui (rice gruel without rice, only barley or millet, mixed daikon leaf or sweet potato vines and some funny seaweed). We traded ration tickets with others for our own needs, ripped pages from prized dictionaries to roll cigarettes with blacktea leaves.

We often got brawled out by editors openly conversing in English. We had to report for weekly military training (crawl around in the dirt in Hibiya Park, jab straw dummies or sandbags with bamboo spears). The personal secretary of the Domei president was in charge. He was a kempei-tai who always called in the delinquents and threatened to have them reported to headquarters. I was a chicken so every kyoren day I would conveniently get sick with asthma which was what returned me to Tokyo from Manila in 1944 after a one year assignment en route to Bangkok which didn’t want a new man. So I got stuck in Manila. My replacement for Ogawa’s English language crew were Murayama, Ishii and Omori. Assigned in Southeast Asia where they eventually ended the war as POWS were Hasegawa, Takahashi, Sawato, Fujii, Ishii, Sasaki.

Otake, in an officer’s uniform with sword at side, was assigned to Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo after a tour of duty in China.

Koito was also serving in China. Roy occasionally dropped in the Domei office during the closing phase of WWII, to exchange information on the war’s development. On his way he’d pass by my desk and say, “No worry, it’ll soon be over. since the office had more His outspoken remarks frightened me than its share of spies and informers. I later learned the reason why Kikou Yamata, a French-Japanese lady, who wrote articles for the Domei French desk next to our section, failed to make her usual appearance. She had been detained by the gendarmerie.

We seldom saw monitored radio copy although at times we had to rewrite copy for newscast that was handed to us. Practically all reports on peace maneuvers were kept out of our hands, also the atom-bomb and earlier reports concerning Japanese citizens and nisei being interned in the U.S., and the exploits of the 442nd boys in Europe.

Mutsu because of illness had been replaced in 1943 and spent the remaining war years in Karuizawa. His replacement was Yasuo (now deceased), an expat from NY, who gave me a hard time after my return from Manila. At a bu-kai meeting I was asked for comments on Domei overseas copy seen in Manila. Like a fool I said it was lousy, etc. Later I was told that Yasuo handled all outgoing copy. I felt like crawling into a hole.

He never forgave me and I was never recommended for a pay raise or year end bonus. After the war we became good friends, apparently all was forgiven.

On Aug. 15 we gathered in the main editorial room of Domei as ordered to listen to the Tenno speak for the first time via radio. We didn’t know what to expect in the gloomy, stuffy room. We stood at attention when the radio as we patiently waited began squawking, followed by an unclear effeminate voice stating that Japan would “endure the unendurable and suffer the insufferable” by accepting the Potsdam proclamation. It took time before it became clear what it meant. There were sniffles and sobs,

Then it dawned that the war was over. Many in kaigaibu who were skeptic about the whole mess from the beginning, sighed a relief then began wondering what was to come.

Some of us thought about getting back to one of our favorite watering-holes, the Locomotive, in back of the Ginza where Mas, Day and Roy initiated me to beer and whiskey with soda or water shortly before Dec. 8, 1941. But the bar was closed in late 1944 as were all pubs.

There’s more, lots more. But I will have to reassemble my disorganized thoughts and refresh my memory. All I can say is that we are lucky we can get-together now and reminisce about an extraordinary period in our lives. (KKT)

June 16, 1986

———————————————————

SHOP TALK AT THIRTY

Quite recently the monthly Domei Bulletin solicited contributions from a varying array of its aging readers scattered all over the country. Sure enough, its editor was soon deluged with a multitude of personal recollections regarding the Domei days. It was a meaningful attempt at leaving behind in black and white what the oldtimers had witnessed and experienced while on duty in the far flung regions under Domei’s dominance.

The editor, however, had to do the sifting as some of them were not quite up to par, irrelevant or impertinent.

In our case there was no trouble of that kind. The contributions were arranged in alphabetical order and sent to the copy-maker. I have to admit, however, I have appreciated what the more the better really means. I went to the mailbox every morning or every afternoon to see if there was anything to pick up. Unlike the Domei Bulletin editor, I was not flooded with responses, but the result was fair enough.

I am hoping that this project be kept up year after year so that a fuller story of our Kaigaibu days may be woven for all interested to read.

It is a wonder of wonders that we are having our second annual reunion in a row. Neither of the groups I helped organize in the postwar years survived beyond its inaugural meeting-party. One was Club Thirty whose members and guests wined and dined, guzzling barrels of beer and cases of imported whisky, in a place, all inaccessible to the Japanese in those days.

Another was Rainier Club formed by those who grew up under the shadow of Mt. Rainier in the state of Washington. The latter had a similar story to tell of its first party. It did crackle only to fizzle off into the thin air.

Meanwhile, I have real with interest all the pieces contained herein. Lt.-Col. Nagai mentioned in the Kobayashi report was subsequently transferred to the Imperial headquarters as chief of Section Four. Col. Nagai surprised me with a gift of money offered out of sympathy for my family.

September 1944 I visited the Imperial headquarters on my way from Okinawa to Manchuria. The Hayashi article refers to the Wake island POW’s. It was Ken’ichi Nakaya who brought word that we were needed in Yokohama to interview them on behalf of the army and navy. I myself helped the army interrogate their young commander and a few others, one of whom gave me his cursory diary as a memento.

As a historian I have interesting documents on file, some of which I have used as illustrations of my articles in print.

They may be reproduced in our coming Reminiscences of the Domei Days. Yours Truly (Chugo Koito)

June 22, 1986